A primer

Debugging and triaging issues in distributed systems is non-trivial – in fact, I’d argue that thinking and building for distributed systems makes most professional software engineer jobs difficult; more than coding. Coding up an application is easy, but not when you run into the scenarios of scalability, rate limiting, large data volumes, or high-IOPS nearRT streams of 1+ million records/seconds.

It’s already difficult getting a single machine to agree to operate the way you want; now, you’re thrusted into a universe involving multiple machines and networks, each of which introduces unexpected failure domains. Let’s dive into some basic issues plaguing such systems.

Message Transmission Failures

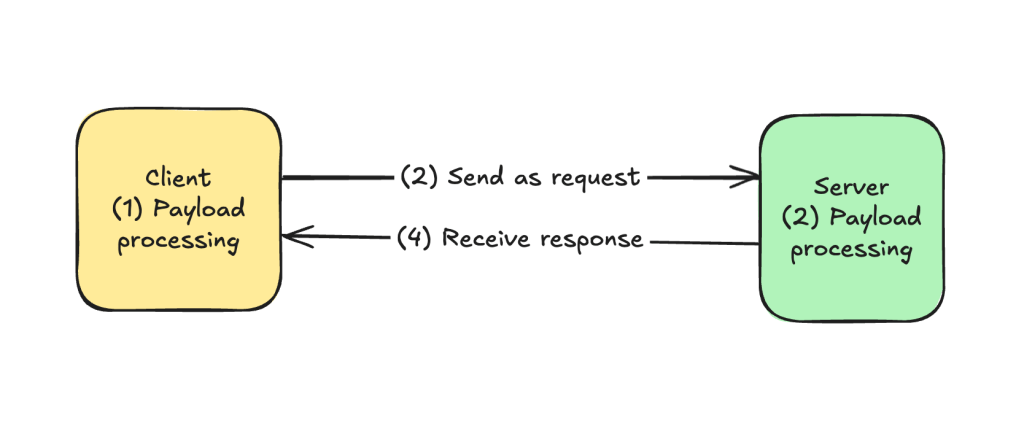

Conducting a root cause analysis on message transmission failures between a single client and a single server is difficult? What’s the cause of transmission failure? Was it even transmission failure? A processing failure? Can we even triage the sources of failures? Let’s look at four failure modes with the simplest distributed system known to people-kind ( yes, women-kind and man-kind ) : two standalone machines/nodes communicating with each other in an HTTP-esque request-response style pattern.

- Client-side process started but fails to process payload.

- Client-side application sends payload over on request, but message drops before reaching server.

- Server-side process received the message, but failed to process succesfully.

- Server-side process sends payload over on response, but message drops before reaching client.

( https://excalidraw.com/#room=60dbd3c682e2803e291f,KU69vHg4E_ifgZp7NvNzSA )

Given this set up, what do we do next?

In the ideal world, where we could run off the assumption that both machines could persist a healthy, long-term network relationship, we can minimize the level of logging, tracing, and debugging. Systems would run smoothly if network communication worked 100% of the time. But that’s not the case. Networks will fail. They fail all the time. And we need to be systems that account for failing networks.

More ever, we typically have access to only one of these machines in most real-world business scenarios. Sometimes, this is due to legal, compliance, and organizational reasons ( e.g. different Enterprise organizations or teams own their own microservices ). Or due to service boundaries when communicating across B2B ( business-to-business ) or B2C ( business-to-customer ) applications. In such a case, we access only a client side application sending outbound requests to third-party APIs or a server-side application processing inbound requests via /REST-style API endpoints ). Logging and telemetry reach their limits too; in a world with four moving components of potential failure, we access only one.

Network Failures

Computer networks can fail for a multitude of reasons. Let’s list them out

- Data center outages

- Planned maintenance work ( e.g. an AWS service under upgrade )

- Unplanned maintenance work

- Machine failure ( from age or overload )

- Network overload ( e.g. (Distributed) Denial of Service attacks, metastable failure, faulty rate limiting )

- Natural disasters – floods, hurricanes, heat waves disrupting components

- Random, non-deterministic sources ( e.g. within Cat-5E ethernet cables, a single packet of light fails to transmit from source to destination ).

Process Crash Failures

- Insufficient machine resources – CPU, Disk, RAM

- Unexpected data volume

- Thundering herd scenario ( DDOS, Prime Day sales, or popular celebrity search spikes ).

- Black swan events / non-deterministic causes – machines aging or single bits at CPU register levels having a one-off error

- Run-time program failures ( e.g. call stack depth exceeded, infinite loops, failures to process object types from callee to caller )

- Atypical or incorrect input formats

- Hanging processing on communication to other components ( e.g. async database read or writes ).

Leave a comment