The Pitfalls of Once-Only Retry

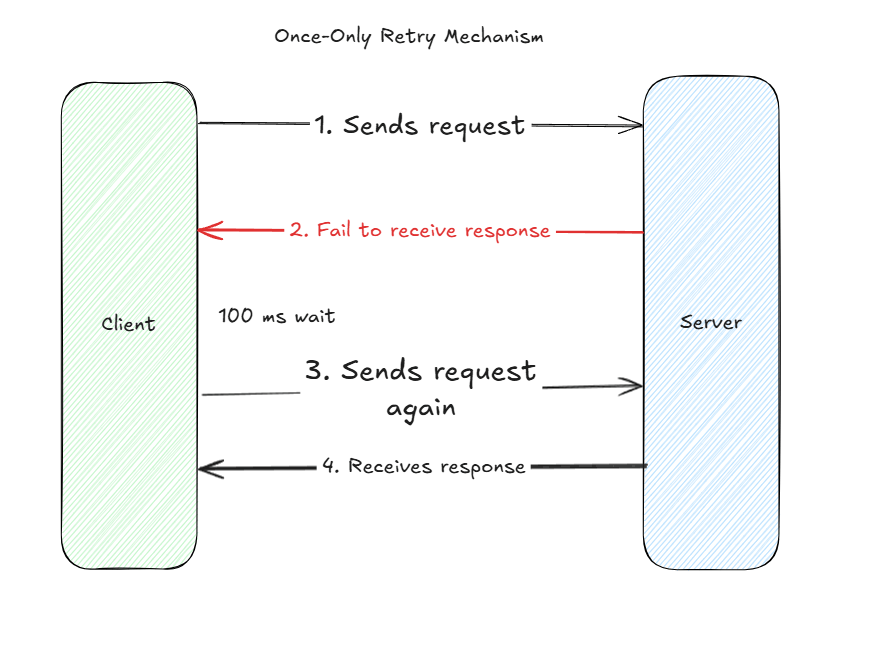

We briefly touched upon the topic of accounting for failures in distributed systems : we can’t always assume that a client application will receive a response from a backend server. We must account for failure. In our world, Bob, a burgeoning junior engineer, thinks about working around a failing system with a quick fix. I’ll just send the request again – immediately after or with a time delay – and wait to receive a response back. Second time’s a charm, right?

Well, in some cases. In the case of success, as shown below, Bob’s client application did receive the response back for the same request. But there’s remains the high failure probability, where Bob’s client fails to receive back a response.

Once-only retry mechanism are quick work around fixes, but they fail to address the elephant in the room – the long-term issues that intrinsically arise from failure modes. Failure modes at the server machine level ( e.g. resource overload ), at network level ( a down ISP ), or a natural disaster ( a data center power outage ).

Migrating to Exponential backoff

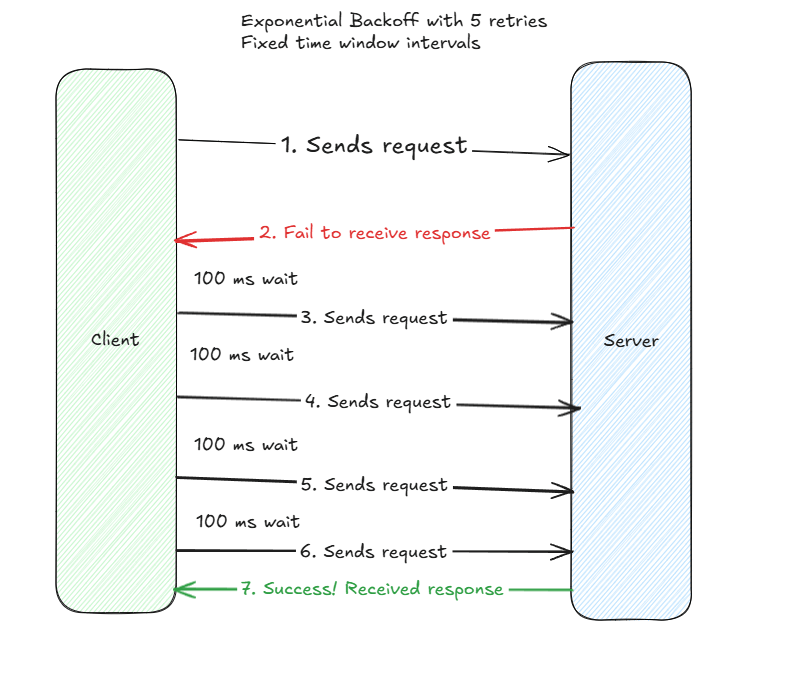

So what does the junior engineer Bob do? He heads over to his technical senior engineer mentor figure, Alice, and asks for technical recommendations and solutions. Alice’s first thought as the technical lead is to reference tried-and-testing industry ideas, such as exponential backoff. She recommends the idea of trying requests more than once, to account for the severity of downstream failure modes. Alright, let’s try out a request five times, with a client-side imposed delay of 100 milliseconds between each delay, and see if we receive a success.

Attempt #1 : Fixed Window Time Intervals

To their astonishment, it works. Hey it took five retries – with a max delay of 500 milliseconds from start to finish – but a request came back at the end! Hooray! Or not!

Nope the real world is a complex beast, and we just ran into a fortuitous case where success happened within our expected time period. The strategy here is a good improvement on the prior strategy, but it’s to rigid.

What if we run into cases where the requests usually come in earlier around the 400 millisecond mark? In this case, can we avoid sending the network requests? What if we can get away sending two?

Or what if they come much later than 500 miliseconds, but still under 1,500 milliseconds? Do we have to send five requests, or can we send closer to four?

A fixed window interval is a good idea, but it lacks in flexibility in terms of both configurability ( only one variable is easily adjustable ) and in real-world applicability. At the scale of a single invocation, changing from 3 requests to 2 requests doesn’t matter much. But at the scale of a billion transactions per day, such as in social media applications, where each request could entail a payload of size 1 KB, we’re talking about a network payloads savings reduction of 1e6*1KB = 1T/delay.

That’s a major savings investment whose gains could translate to markedly reduced operational expenditures! And not only in terms of network, but even with respect to saved compute cycles for other concurrent operations, whilst still meeting end user Service-Level Agreements.

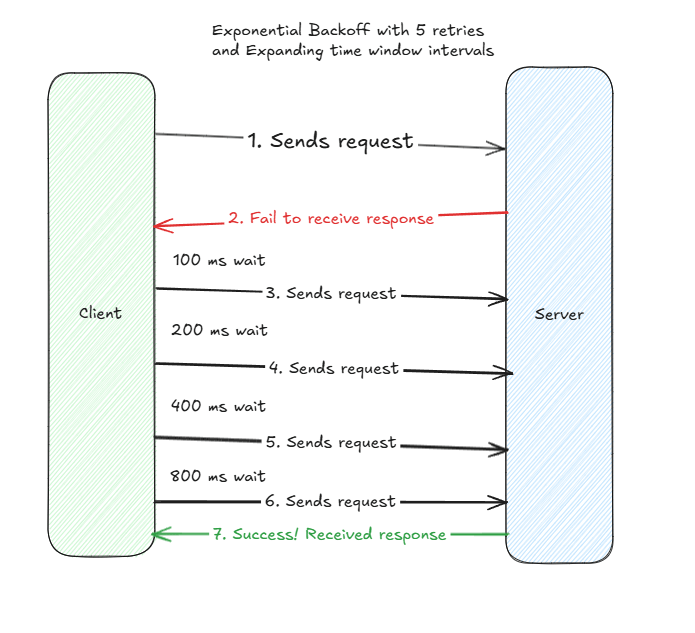

Attempt #2 : Leverage Base and Power to Increase Success Probability

Ok so we covered a fixed-window based exponential backoff strategy. But in the real world, a downstream service is unlikely to be up so quickly ( in the event of black-swan events of outages ). Client’s may also be able to afford additional wait periods for future request attempts, provided that a response can be returned within a final time window ( e.g. if I allocated 1 second of request-response time, I can theoretically wait for 900 milliseconds for successful processing.

Let’s return to Alice the TL again. Alice collaborates with a staff engineer on her team, Sam. With Sam’s help, they agree on leveraging an exponential backoff strategy, where in place of a single constant for a fixed time-window, they use the combination of two variables – a base and a power – to increase each successive retry execution. For example, with a constant of 100 milliseconds, a base of two, and a power cap of four, they build for retries following a mathematical sequence : 100*(2)^0, 100*(2)^1, 100*(2)^2, 100*(2)^3 – corresponding to 100, 200, 400, 800. Now the client’s will know at run-time how much wait time to endow for each successive request if it fails to receive a response back from a server.

And the strategy works better. Alice, Sam, and Bob observe that exponential backoff outperforms both once-only retry and fixed time-window strategies. They take notice that in the cases that responses come back earlier ( e.g. 400 milliseconds ), they send fewer requests, and in the case they return back later ( e.g. 1500 milliseconds ), they can still expect a response back in the event of success.

What to clarify and ask when migrating over to new strategies?

- Do we still meet expected SLAs or SLIs for our end customers if we choose to leverag a new retry strategy. For example, if we have to meet a latency SLA of <= 200 ms time, we can’t configure for 100ms of wait between 5 retries of exponential backoff? We either (A) need to configure shorter time periods or (B) need to configure for fewer.

- How do we determine the optimal base and power? There’s tradeoffs to selections.

- To big of a base or power – increasing latency and application performance degradations

- To small of a base or a power – increasing failure likelihood; inability to account for cases when a downstream service could have had a working response ready if we provided a bigger buffer window; failure to retrieve responses for critical upstream clients.

- How do we account for failed requests, even with exponential backoffs? Do we immediately error out to upstream clients? Or do we leverage techniques such as DLQs ( Dead-Letter Queues ), where we store the requests for future analysis? Do we retry failed requests on a later time or date ( perhaps one or two days from now ) when systems will be up and running ?

- How do we balance the priority of old, failed requests in an exponential backoff loop with continuous new, incoming requests? We can’t always let old requests take the highest precedence without new requests accidentally ending up in the exponential backoff scenario? Can we set up for optimal prioritizations in our request queues? This entails a transformation from a regular FIFO – First-In, First-Out – Queue to a priority queue, but can lead to performance gains and meeting end user requirements.

In Conclusion

Overall, I made good argument with accompanying visual diagrams for why to consider exponential backoff over once-only retries or fixed time window interval retry strategies. A battled-hardened, tried-and-tested industry strategy, exponential backoff serves as a solid foundation for making quick improvements to major infrastructure problems. It’s use cases – social media applications, data engineering pipelines, or payments processing flows – further supports its consideration.

References :

Exalidraw Link : https://excalidraw.com/#room=c24d2cf7aa80b854542a,dl2NkWc-cilvzptmi1dLQw

Leave a comment