Because I’m just as sick of seeing questions that remind me of inapplicable problems, like shooting penguins out of cannons in your AP Physics Textbooks, and I’d rather solve something that entails more pragmatic engagement.

Why real-world applicability?

Today, I want to share one of my favorite leetcode problems to solve, and why I think it’s a worthwhile problem to stress test possible candidates. Since I’m someone who’s solved a boatload of Leetcode problems, I’m always thinking about how interviewers can select for better problems and index for candidates who demonstrate better real-world, on the job performance thinking skills.

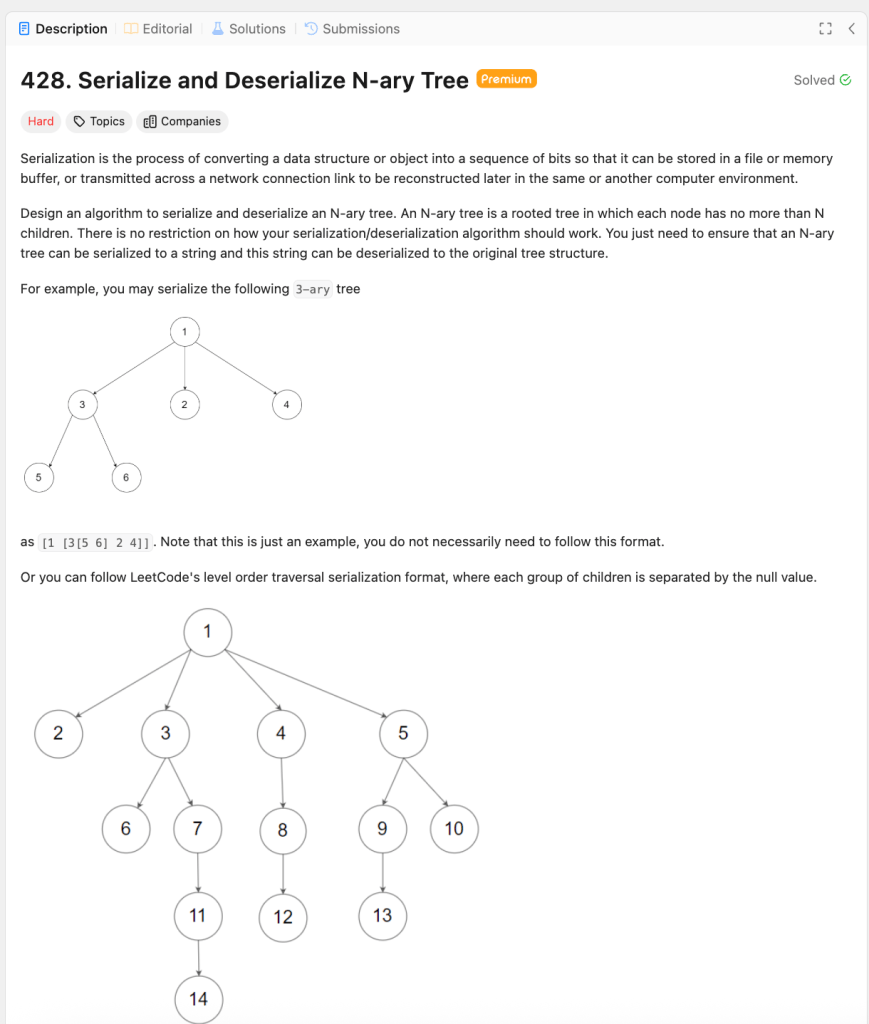

The problem is Leetcode 428. Serialize and Deserialize a N-Ary Tree. I’ve attached the description underneath, but in this problem, TC ( the canidate ) needs to be creative and conjure up their own approach to serializing ( converting from an in-memory data structure to a string ) a n-ary tree and then deserializing said tree ( converting back from a string to the original structure ) . It’s technically a HARD category problem, but in my honest opinion, it borders a hard MEDIUM difficulty question. I would definitely ask it to a Google L4+ candidate ( using current leveling systems ). I think this is a good problem because we stress-test the following criteria :

The Stress-Test Criteria

- Word problem translation – the description closely mirrors real-world case studies and ambiguous problems engineers encounter. Without the constraints mention, TC can spend some time asking really good clarifying questions.

- Design thinking open-endedness – candidates can get super creative with their approach ; their really is no “one-size-fits-all” strategy, meaning that there’s room for an interviewer to possibly learn how to do a problem differently ( and maybe better ). My approach involves a root-left-right style with more paranthethicals : it resembles (1 (3 (5) (6) ) (2) (4))

- Real-world applicability – thinking of how to handle serialization and deserialiation, or at least handle converting structures across multiple formats ( e.g. JSON to memory or in-memory to Protobuf ), is frequently encountered when transmitting payloads across environments.

- Recursion – in the general, most good interview problems stress test recursive thinking.

- String handling -TC needs to think about parsing strings – how to handle the different tokens ( integer values, ‘(‘, ‘)’, ‘,’ ). This may entail the use of Regexes or a combination of library functions and delimeters. It also involves conjuring up a rules engine to adjust a pointer in string input, based on the token under processing.

- Top-down/ bottom-up chunkification – TC needs to think about how to segment the input in their recursive-esque approach.

- Compression – interviewers can gauge how well TC think of making minimal serialization strings. This matters in the real-world with at-scale settings, where input compressions translate to revenue.

- Minimal data structures – the problem is solutionable without data structures ( implicit stack space recursion ) or with a stack ( explicit memory recursion ). There’s minimal “trip up” room in TC needing to think of to many data structures.

Footnotes

URL Link = https://leetcode.com/problems/serialize-and-deserialize-n-ary-tree/description/

![PERSONAL – so how should we assess & evaluate engineers? Good question – it’s definitely more than just lines of code [ LOC ].](https://harisrid.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/generate-a-featured-image-for-a-blog-post-about-evaluating.png?w=1024)