The Value of Writing – a Primer

Hi all!

Today, I’m going to delve into another topic – writing!!! Yep, writing!!!!

Yep, the subject you ( probably ) badly wanted to avoid back in high school and college. The dreaded dark days when you read classical literature like Moby Dick or All Quiet on the Western Front and write out long-form essays, reflections, or short stories on the books your teacher assigned.

Well, it turns out that writing is a crucial skill for engineers. In fact, I’d argue more important than coding ( especially with the advent of Chat-GPT and GenerativeAI tools that can quickly spit out code ). Many of us share this feedback with each other – the best engineers are solid technical writers. They’re not just good coders. In fact, they may not even be your team’s best coder. Someone more junior might have shipped out more LOC – lines of code – then them during their entire tenure!

But the best engineers sure know how to write. They’re good at convincing multiple audiences – engineers, product owners, leadership and management – that their ideas are “worth their salt”, that their system designs are solid, and that their user stories make sense. Their documentations serve multiple roles – mentorship, conveying impact, and tracking accomplishments.

More ever, seniority and leveling naturally endows writing. Your role responsibilities -coupled with the folks you collaborate with ( senior talent ) – will act as a “forcing function”. You’ll either get tasked out – or create the task yourself – to write up up design documents and technical specifications. Writing at the high level is ineluctable ( and inescapable ).

Lastly, it’s not a bad thing. In fact, I argue that writing is good. Think about it – the most famous people in your life and in your profession write. Barack Obama ( former US president ) has to read and write. Roger Penrose ( renowed astrophysicist ) wrote The Road to Reality. And Thomas Cormen wrote the bible of algorithms – CLRS. Emulating your profession’s titans is a good starting place!

But what do I write about? How do I get started?

But what if I run into writers block? What if I can’t find a topic to write about.

That’s a good question. Let’s tackle that too!

- Write about what you learned – did you create a side project in your free time? Contribute to a long-running OSI ( open source initiative ). Did you engage in a fascinating project back in your undergraduate days? Write about your learnings. What were your challenges? What were your biggest takeaways?

- Write about what you know – Finding topics is a hard subject, but start from what you know. Words flow out easily from a priori established knowledge bases. Look into starting with topics from your day-to-day work – this can help you in a few ways. Writing about your work, outside of work, not only helps you better understand your work, but enables you to deliver faster on your work deliverables ; it’s a positive feedback loop in the hiding!

- Write opinion pieces – do you have a technical opinion? Something you want to share? Do you want to talk about what you think makes for an effective design document? Or how to make good user stories? Perhaps even a dissenting opinion ( gaaaspp, turns out you can disagree with engineering best practices, because a best practice isn’t a best practice in all situations ).

- Write about engineering best practices – there’s a lot of good engineering practices out there, and every engineer knows a good habit or two. I’d be hard-struck to say that I’ve met an engineer who never taught me a better technique in coding, debugging, designing, or investigating issues.

How to Refine Your Technical Writing Skillz?

- Practice, Practice, Practice – the best way to get better at technical writing, is to practice writing. Practice makes perfect. Find opportunities to engage in technical writing. This can include outside your company.

- Solicit feedback – the best writers don’t operate in a vacuum; they solicit and ask for feedback from their peers. Peers can see things that you don’t see in yourself – the good and the bad. I’ve asked for feedback in the past, and I’ve gotten examples such as

a. Be concise and clear – shorten sentences and write less verbosely.

b. Think about your audience – write different types of documents, based on the audience? You can set topics for documents – brainstorms, condensed, and expanded versions.

c. Focus on the big picture – shift your focus away from the low-level details towards the bigger picture.

d. Write about today and tomorrow – write about problems from a timeline perspective – what does the current state of systems look like today, and what do we want those systems to resemble tomorrow?

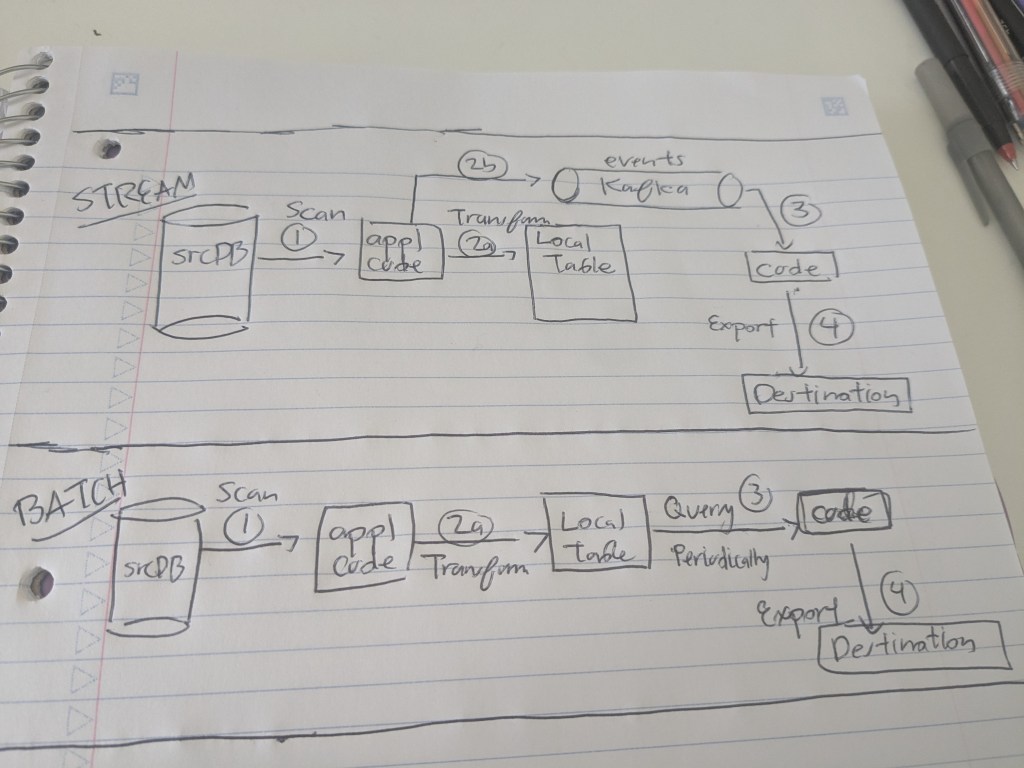

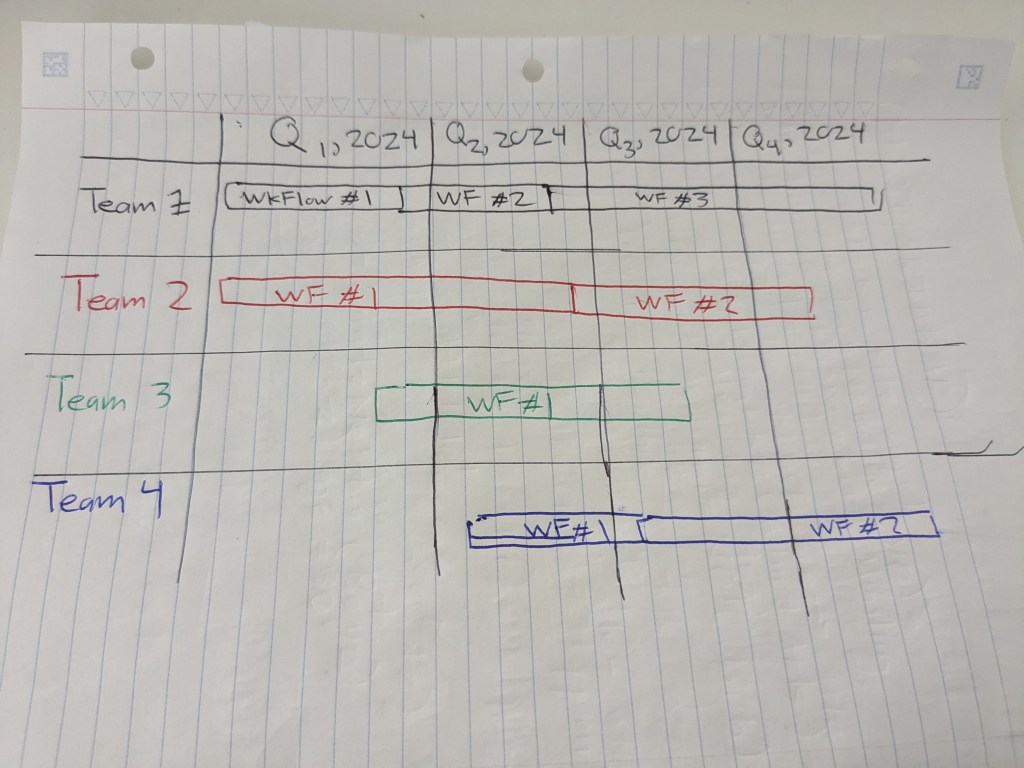

e. Incorporate visuals – focus on capturing reader attention to convey your points more effectively – leverage state transition diagrams, system diagram, and tables. Color-code and label the visuals too. - Read ! Read widely! – are there examples of engineering writing you admire? Books whose styles resonated and “clicked” with you? Blogs that captured your interest? I strongly admired these blogs 1for their specific traits :

a. Communication styles – Gusto ( https://engineering.gusto.com/ ) and AirBnb ( https://medium.com/airbnb-engineering ).

b. Communication Simplicity and openness – the mathematical blogs Better Explained ( https://betterexplained.com/ ) .

c. In-depth expositions written out in Professor Scott Aarson’s blog ( https://scottaaronson.blog/ ) .

- I still consult these blogs – and other online media – from time-to-time 🙂 ↩︎