A Primer1

Let’s imagine a scenario that could happen in the real-world.

Ximena, a mid-level engineer, works at a banking company which leverages AWS as its cloud-hosting provider for infrastructure and scalability. She’s debugging the latest feature released to production; she’s spending a large chunk of her time performing root cause analysis and filtering out log files on AWS CloudWatch and Enterprise-logging software tools such as Splunk and New Relic. A couple of minutes into scrolling through the log files, a lightbulb flashes – she realizes something! “Wait second”, Ximena thinks to herself. “I can change the structure of our future logs and spend less time parsing and analyzing files. I bet this move could save time across the board and help my organization reduce it’s cloud spend.”

Ximena, feeling excitement, quickly schedules out a 15-30 minute Outlook meeting. She briefly introduces her ideas to two other mid-level engineers, Chichi and Faisal. The three engineers collaborate; they engage in back-and-forth discussions, with Chichi and Juan offering advice and asking a few clarifying questions to Ximena. Both her other mid-level engineers love the idea – reducing log bloat. In the end, they all agree to it.

Next week, changes to the codebase are noticed. Log files take up less space, and developers feel less pain triaging haystack-in-a-needle types of issues 🙂 !

So how much are we saving? You got the numbers or the storage calculations?

Alrighty then! Let’s imagine the differences of payloads we’re logging and make a few assumptions. Let’s assume we generate log files daily for a global event stream and that business requirements mandate the retention of logs in S3 for one year before transitioning them to compressed archival storage systems.

- 1,000,000,000 ( 1e9 ) events processed daily in an event stream

( think of a high-frequency trading firm processing 1B+ events for the NYSE or other major stock exchanges ) - A production-grade stream expected to service an application for one year.

- Request payload size = 1 kilobyte ( 1e3 bytes )

- Request metadata payload size = 100 bytes ( 1e2 bytes )

- Response payload size = 1 kilobyte ( 1e3 bytes )

- Response metadata payload size = 100 bytes ( 1e2 bytes )

Wait but when does a request or response reach 1 kilobyte in size? Ok maybe that’s not the case for your personal apps, but enterprises frequently deal with large JSON or large XML payloads to retrieve analytical reports. They can get large.

Storage calculations for logging with raw request and response payloads :

1e9 events/day * 2 payloads/event * 1e3 bytes/payload * 365 days/year = 7.3 e14 bytes/year = 730 TB

Storage calculations for logging with request and response metadata :

1e9 events/day * 2 payloads/event * 1e2 bytes/payload * 365 days/year = 7.3 e13 bytes/year = 73 TB

That’s a factor of a 10x reduction in log file output. Woah.

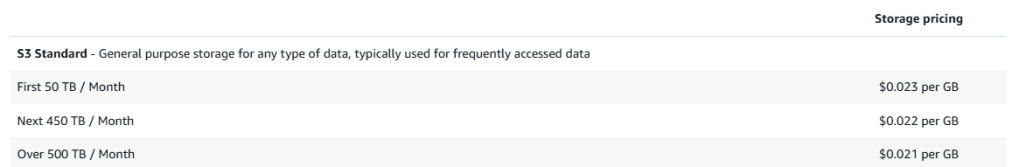

For the sake of calculation, I’ll just use the first line item for pricing. We can view a cost delta of (0.023) * [(730 * 1000) – (73*100)] * (1 month / 1 year ) = $1,385 / month. WOAH! Multiply this over a year, and we get a delta of $16,622.1 per annum. There’s a huge savings potential there in the range of $10K+ in annual revenue netted by removal of log bloat.

The benefits of log bloat reduction!

- Reduced cloud expenditures – exorbitant cloud costs pose bottlenecks for companies wanting to build out feasible solutions. Lowered cloud expenditures enable more customers to best utilize cloud offerings2

- Expedited developer velocity – developers can spend less time filtering, grepping, parsing, or searching through large collections of log files. It indirectly translates to faster coding, debugging, and product-ionization of applications.

- Output data flexibility – logging less data means fewer restrictions on what we need to output or take as input from log files. Request metadata schemas, for example, and more flexible than request body payloads.

Conclusion

I made a strong justification for why software developers should cut down on log bloat, as well as look into subtle optimizations that can be made on logging and infrastructure. The work is less appealing than coding up and productionizing a new feature under your ownership, but, the potential cost savings at scale and the reductions in wasted dev cycles can be mind-boggling! It’s worth taking a look!

- This scenario did happen – credits to my co-worker Jaime for noticing this optimization. ↩︎

- It’s complicated for the cloud companies here in terms of whether log bloat reductions help them net a profit. Cloud companies would loose on profits earned on specific services ( e.g. AWS Cloudwatch ) since less data would be dumped into Cloudwatch log files. But cloud providers could earn profits elsewhere; their customers could divest spending to other cloud capabilities of specialized offerings. I hypothesize that avoiding log bloat is a win-win for both cloud providers and customers. ↩︎

Leave a comment