“It is difficult to see the picture when you are inside the frame”

Communicating your strengths and your weaknesses to anyone – especially in an interview setting – is difficult ( for the majority of us, some of us find this easier ). But how do I know what I am good at versus what I am bad at? No one else has ever explicitly told me what I’m good or what I’m bad at.

It’s hard to gauge – especially when you can look at only yourself. But experiences when working with others can be especially enlightening and you may start to make a couple of observations. Such observations are going to be surprisingly correct. Alrighty then, let’s dive!

My Strengths

Everyone is good at something.

When at least five other people in your life tell you that you’re good at something, you’ll know you’re good at something.

- Fast Pattern Matching – I am a very good pattern matcher! I was fascinated with patterns as a kid, and I love to think in patterns – data, trends, plots, etc., Patterns are super informative ; they help me optimize and make the best decision.

- Strong observational skills – I absorb, observe, and take in a lot of information from my environment; it enables me to enact rapid decision-making. I’m always learning and noticing things; it never stops.

- Analytical thinking – I love analyzing things. I love asking why. Why ( but really, Tell me why ) is my favorite question to ask. There’s always a reason for why things are the way they are.

- Associative thinking – harkens to pattern matching, but I like to think in associations ; if X is related to Y, and Y is related to Z, X has a relation to Z. Or take a word – conjure. My verbal associations are : Dungeons and Dragons, Wizards, Magic, or Fantasy. Think of drilling down the links of wikipedia across different topics 🙂 . Associative thinking lets me make connections in places that folks don’t typically connect.

- Abstract and Mathematical Thinking – I was a math major back in my undergrad days, and I leverage mathematical language to communicate ideas that might otherwise be hard to digest. Formalism, invariants, and a logical chain-of-thought reasonings boil down complexity into simplicity and enable peers towards quick understandings.

- Multi-perspective/Multi-lens thinking – I’m talented at viewing problems or challenges not just through my lens, but the lens of others – those coming from different audiences, backgrounds, and skill levels. It let’s me tailor my communication accordingly so that the other party understands execution and deliverables.

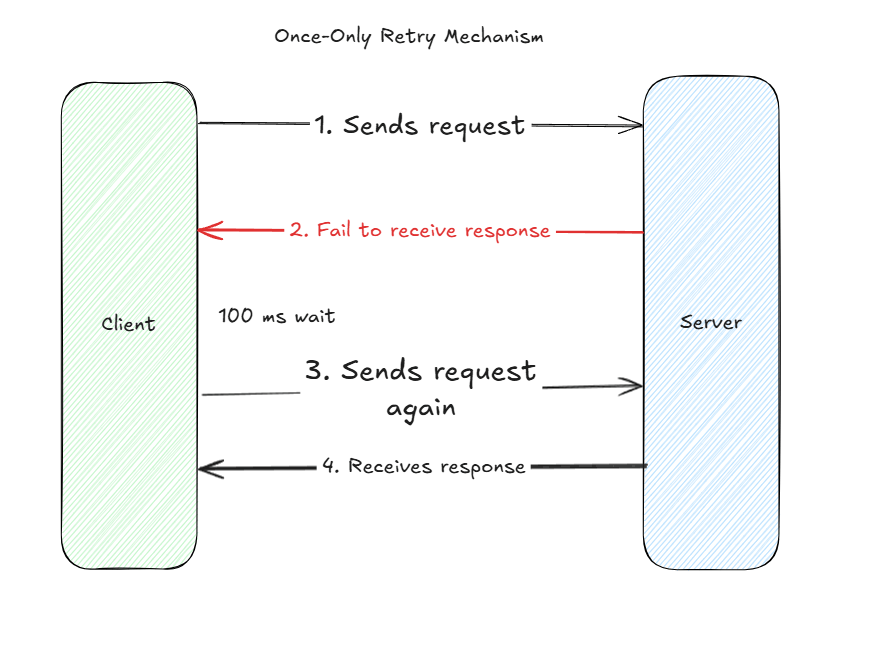

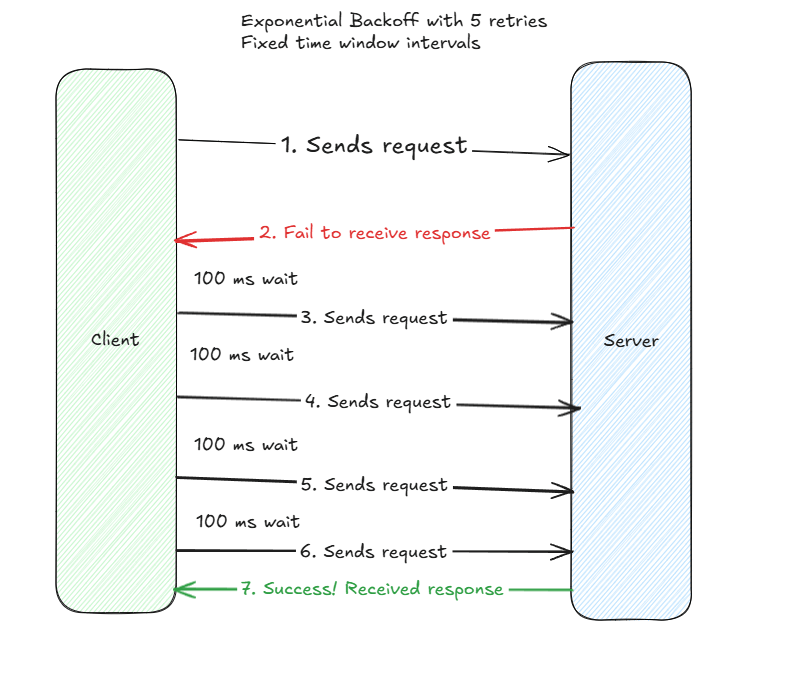

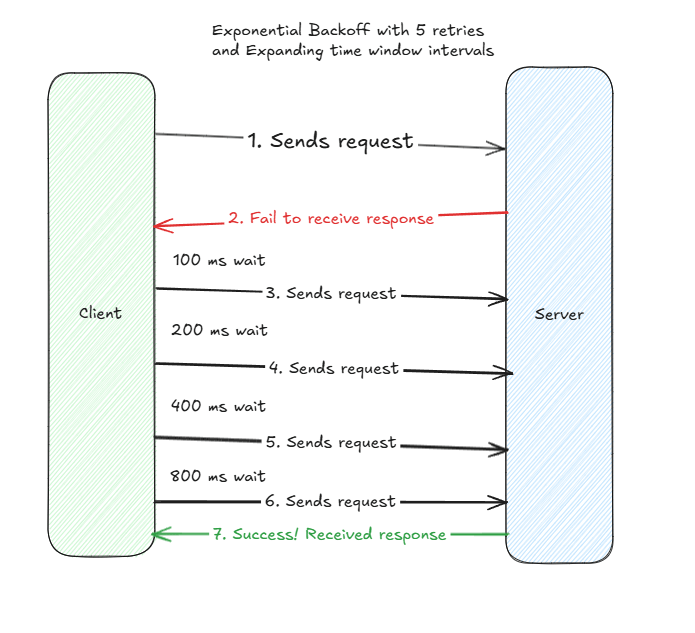

- Anticipating Future Scenarios; thinking about hypotheticals – When I built code, I like to think of all the ways something could fail or go wrong. Hey, do I need to think about input sanitization/validation? Do I need to think about bad actors? What if situation A happens? What if in three months, we have to suddenly shift to situation B?

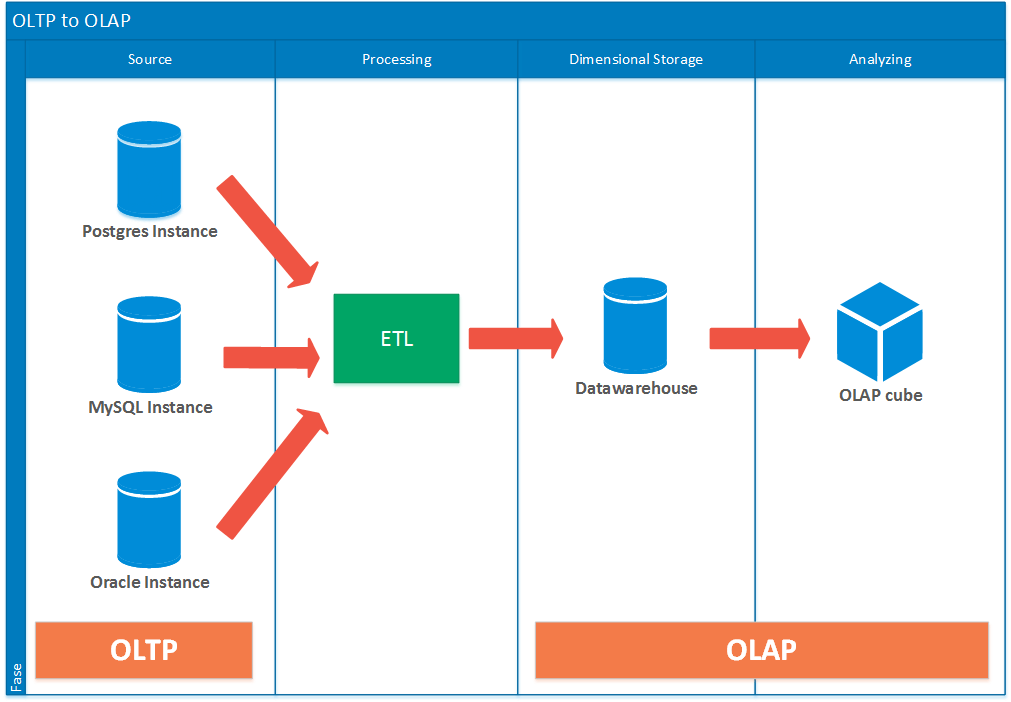

- Detail-oriented thinking – I’m good at zooming-in and honing-in on specific system details ; I build up a comprehensive picture of complex systems from multiple smaller, independent units of systems.

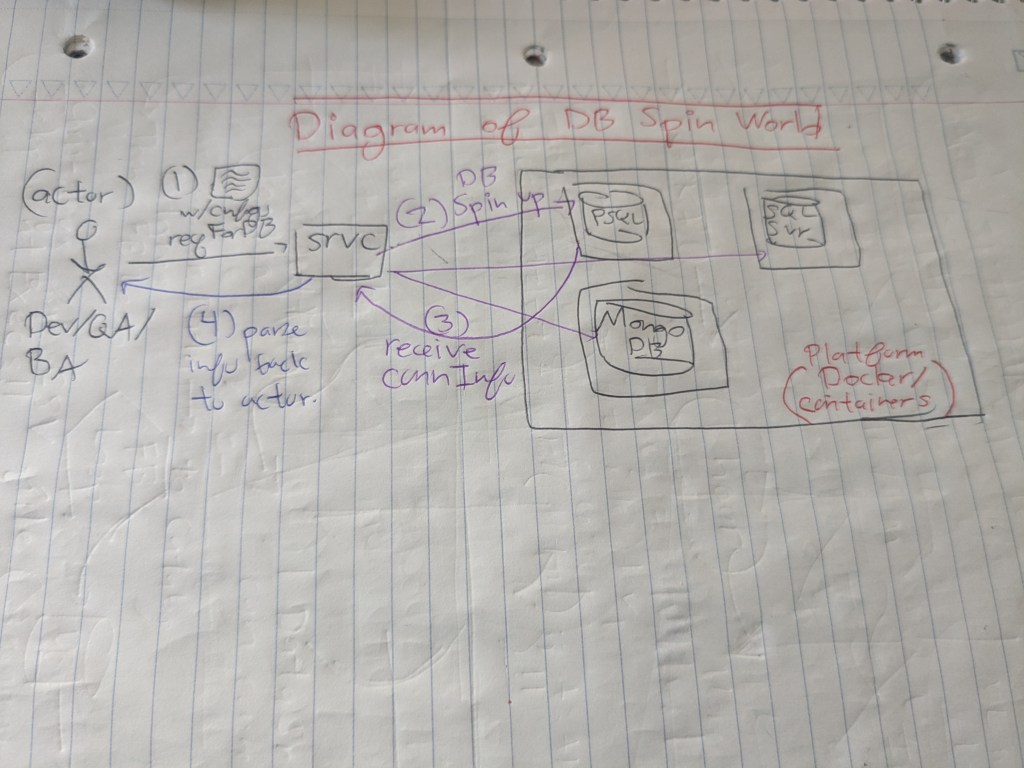

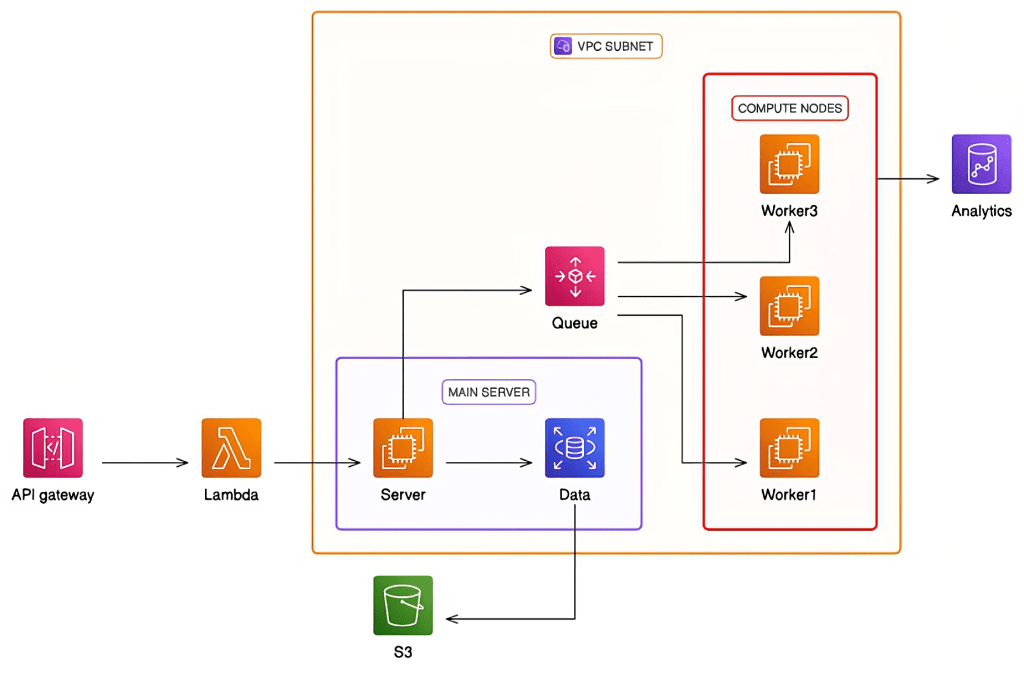

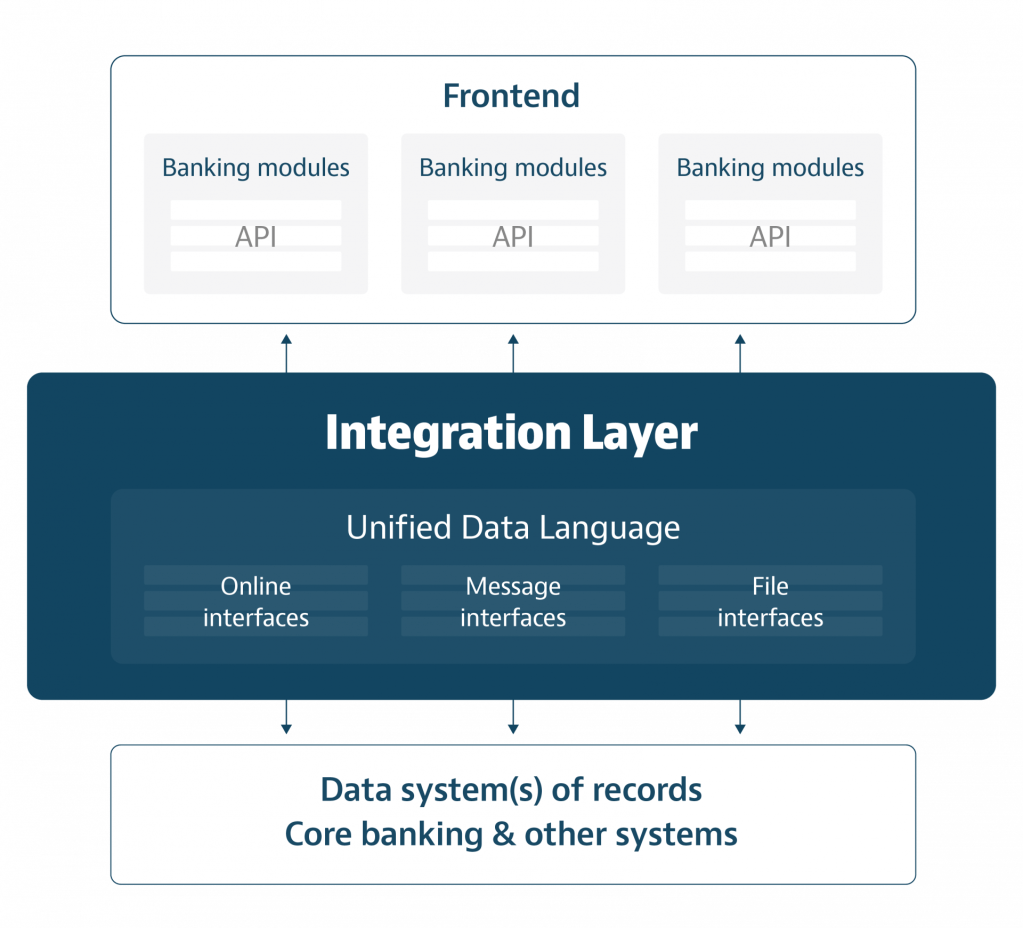

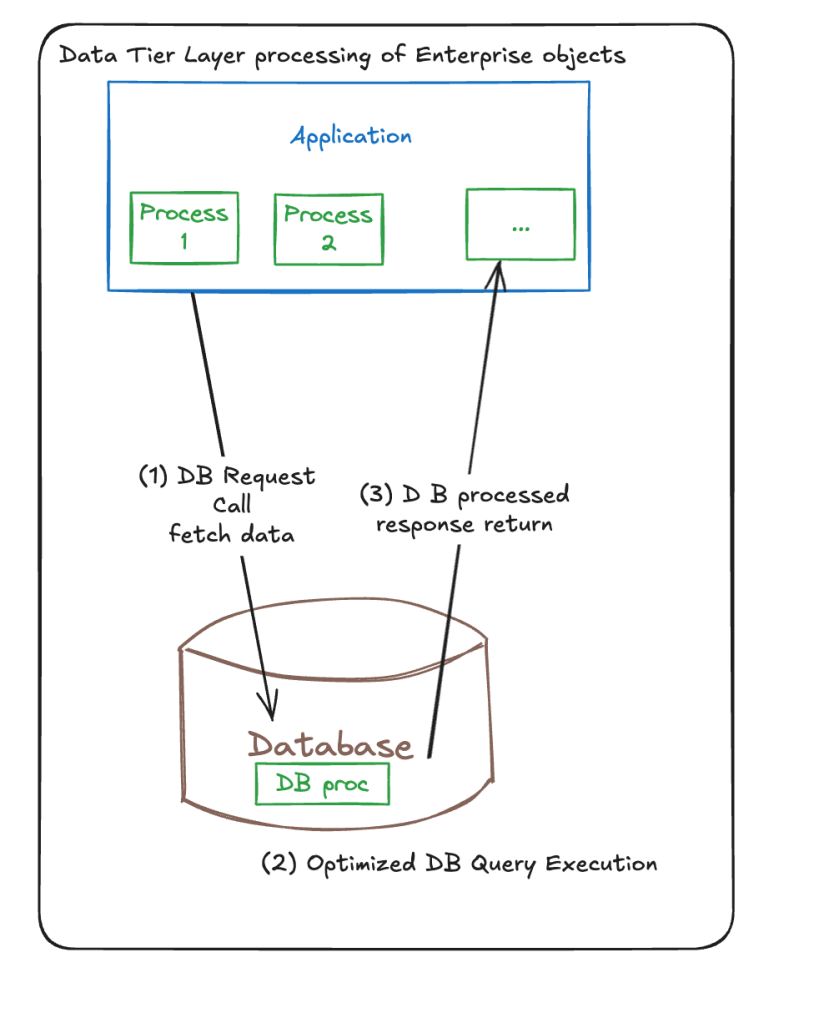

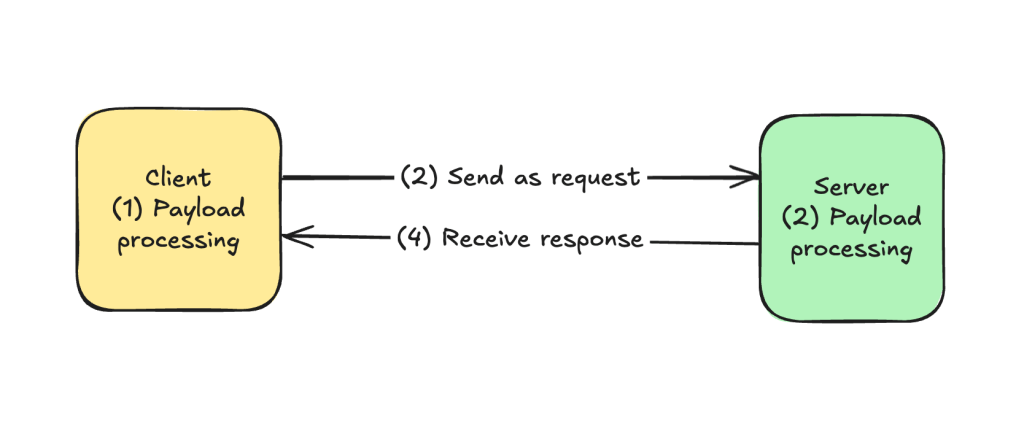

- Visual Thinking & Diagramming – I’m good at whiteboarding and diagramming systems and moving components. I can throw an architecture diagram and make quick changes to arrows or textual descriptions while listening to more senior folks on my team.

- Mentorship & Teaching – I love helping getting other people unstuck on what I do well; there’s a boost of dopamine I get when I see the lightbulbs flash in someone else – suddenly, they can connect the dots and see what they couldn’t see before. It’s like I helped someone re-wire their brain ; I changed their mental circuitry 🙂 ! When I was a senior engineer at Capital One, I helped a junior engineer deliver change lists faster and taught best coding practices and unit testing practices ( e.g. testing both the happy paths and the sad paths of code ). Over the course of weeks, I noticed improvements in their code velocity and reductions in code review cycles.

- Technical Writing and Documentation – I’ve had at least five different people tell me that I’m well-read and a solid writer. I like to tell others about the story where I was a L3 software engineer at Google, and my L5 senior software engineer told me that I wrote really good documentation on my project.

- Communication – when I was practicing interviews on interveiwing.io ( at the time ), I got feedback that while I wasn’t the technically best person, I communicated my ideas effectively. I’d see ratings of 4/5 for technical skills BUT 5/5 for communication skills.

- A good conversationalist – I’m good at holding a conversation and speaking to others. I always have something to say, to share, or to talk about. I can talk about a wide ( and I mean a WIDE ) variety of topics. You’ll never have something to not be able to talk to me about

- Encyclopedic– I’m told by others that I know a lot of pieces of information here-and-there. I rapidly connect topics across different places – perhaps unrelated.

- Leading Meetings and Collaboration – I’m a very extraverted and social engineer. Sure I like independent coding, but some of my best work is done in lockstep with others and NEVER in isolation. This includes past class projects and past work experiences. There’s always something that I learn when I pair program or develop solutions with other talent. If you need me to run a meeting, set the agenda, and get five people in my room, COUNT ME IN!!!

My Weaknesses ( a.k.a. what I’m working on )

No one is perfect.

Everyone has a “crack in one’s armor” : an “Achilles’ Heel”, so to speak. We all have weak spots and vulnerabilities.

Alrighty then, let’s get to the part we’re more scared to talk about ; the can of worms – our weaknesses!!!

And oftentimes, let’s make a difference. Weaknesses aren’t always what they are. Maybe you just haven’t practiced a skill as much due to a lack of exposure of practice environments. Or you just didn’t need a skill in one environment, and it’s showing up in another environment.

- Analysis Paralysis – when there’s so many solution paths ( e.g. 10 different ways ) available to solve a problem, which path should we select? Should I select for the best? Go for the first one available? Or immediate bias to action? Do I need peer feedback, or can I dive-in and independently execute?

- Task Delegation – when you’re experienced, it’s easy to quickly execute on tasks. But no one can do everything in the world, and impact is made by being a force multiplier and getting large groups of people to deliver on long-term organizational goals.

- Downplaying impact – I tend to downplay my impact at work or the complexity of my tasks, but I fail to see that what’s easy for me isn’t always easy for other people, and that what I did really was a complex task. And sometimes, not just technically complex or in coding – maybe in systems thinking, working across stakeholders, or juggling multiple deliverables.

- Task Decomposition – Learning to break a large, ambiguous, long-term task into smaller, more concrete tasks is still a hard skill. I’ve improved with a combination of practice, exposure, and feedback from others more skilled than me. Good advice has been to engage in development in phases ( e.g. phase #1, phase #2, and phase #3 JIRA tickets ).

- Prioritizing Goals – Sometimes I’m working on a unit of code or a feature under development, and I get an update during a Sprint ; all hands need to change tasks to a completely different feature under development. Which I don’t mind, but I’m the type who likes to still work on what’s fresh on my mind and interesting. I’m working on context switching and combating the feelings of frustration with having to jump across tasks, versus keeping on my task of interest.

- Keeping the context and avoiding small details – sometimes I get side-tracked and look a bit to much into other systems. It’s a good thing ( for learning ), and sometimes, those side-tracks and tangents are useful. But in the grand scheme of the things, I need to shift focus to smaller areas and focus on the end goal – the deliverable. There’s a lot to learn and look into – meaning, there’s a lot that you don’t need to learn and look into.